- Exploring The Inner Game with Adam Carmichael

- Posts

- How Much of My Striving Is Really About Being Seen?

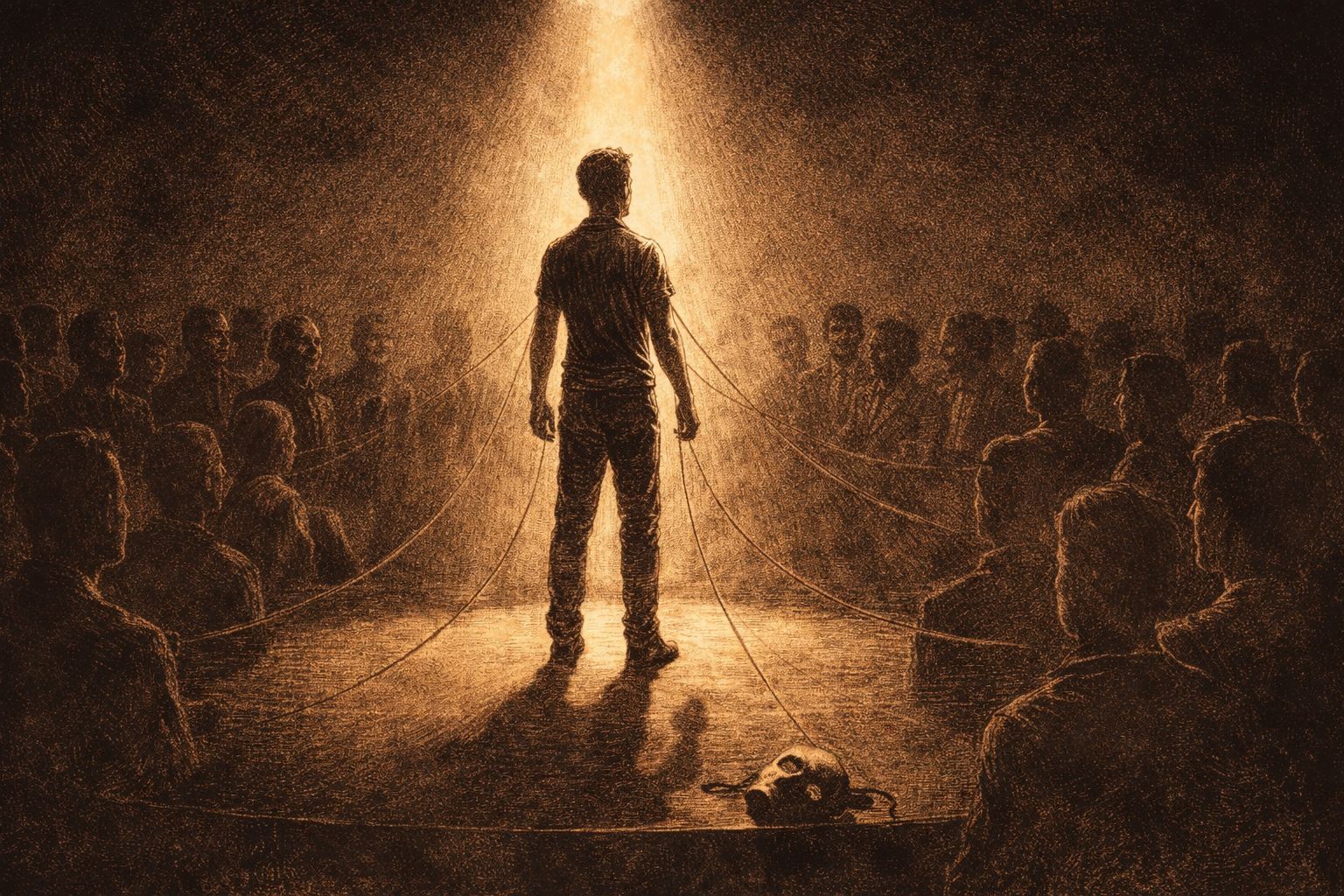

How Much of My Striving Is Really About Being Seen?

I recently started reading The Courage to Be Disliked.

I’d seen the book mentioned plenty of times before, usually framed as something about confidence, boundaries, or learning not to care what people think. I assumed I already understood the message well enough and never felt much urgency to pick it up. I was wrong.

What I didn’t realise is that the book is really an introduction to the work of Alfred Adler — a psychologist who was a contemporary of Freud and Jung, yet somehow feels largely absent from modern psychology and self-development conversations. And the more I read, the stranger that absence feels, because his ideas don’t come across as outdated or abstract at all. If anything, they feel uncomfortably modern.

Adler wasn’t particularly interested in digging endlessly into the past or analysing unconscious symbols. His focus was simpler, more relational, and in many ways more confronting. He asked questions like: How do we live with other people? Why do we suffer in relationships? And what are we really trying to achieve through our behaviour?

As I worked through The Courage to Be Disliked, I noticed something interesting happening. I wasn’t highlighting clever ideas or trying to memorise concepts. Instead, I kept pausing, closing the book, and turning the lens back on myself — on my ambitions, my relationships, my role as a coach, and the subtle ways I relate to other people on a day-to-day basis.

One Adlerian idea in particular stayed with me. Not because it felt profound at first, but because it wouldn’t leave me alone.

One of Adler’s core claims is simple, almost confrontational:

All problems are interpersonal relationship problems

When I first read it, something in me immediately agreed. Not intellectually, but viscerally. The more I sit with it, the more it feels like a quiet truth I’ve been circling for years without ever naming directly.

Because when I really look at my life — my stress, my striving, my restlessness — so much of it only makes sense in relation to other people.

It feels increasingly clear to me that how we see ourselves is largely shaped by how we imagine we are seen. If we were deeply, genuinely accepting of ourselves, would we worry so much about what others think? Would we spend so much energy managing impressions, proving competence, or seeking validation?

Probably not.

And yet, so much of modern life seems organised around achievement, status, approval, and recognition. We call it ambition. We call it growth. We call it self-improvement. But Adler offers a different framing, a one that’s harder to hide from.

The real reason we are striving

He suggests that much of this striving is really about feeling important, or perhaps more accurately, about protecting ourselves from a feeling of inferiority.

That word can sound harsh at first. Inferiority. As if it implies something broken or pathological. But Adler didn’t mean it that way. For him, inferiority is simply part of being human. We begin life small, dependent, and unsure of ourselves. The question isn’t whether we feel inferior, but how we respond to that feeling.

And this is where things started to get personal for me.

I’m someone who strives. I like progress. I like getting better. I enjoy setting goals and moving toward them. On the surface, this looks healthy, disciplined, even admirable.

Take the gym. On one level, I genuinely love the process — the structure, the consistency, the slow accumulation of effort over time, the satisfaction of becoming stronger. There’s something deeply grounding about it.

But if I’m honest, that’s not the whole story.

There’s another layer there too. I enjoy what getting strong says about me. I enjoy the identity. I enjoy the story I can tell — to others and to myself. I enjoy how it positions me socially, how it makes me feel competent, impressive, respectable.

And that raises an uncomfortable question.

If this striving is purely about growth and self-expression, why does it feel so tightly bound to being seen? And…

Is growth always tied to being seen?

Adler would suggest that striving and inferiority are often two sides of the same coin. Not in a moral sense, and not as a criticism, but as a psychological reality. Much of what we call ambition is relational. It exists within a social field of comparison, status, and meaning.

That doesn’t make it wrong. But it does make it revealing.

I found myself running a slightly disturbing thought experiment.

I imagined achieving my biggest powerlifting goal, which would be to win the World Masters Powerlifting Championships when I turn 40. I pictured the recognition, the respect, the subtle but unmistakable shift in hierarchy. There’s a part of me that lights up at that image, and that part doesn’t feel particularly spiritual or evolved — it feels very human.

And then another part of me asks: what exactly is that feeling? Is it pride? Is it joy? Or is it a sense of superiority?

Is that something to be celebrated? Is it something to be ashamed of? Is it inevitable? Is all desire rooted in a sense of lack?

I don’t have clean answers to those questions yet. But Adler doesn’t seem interested in offering comforting conclusions anyway. What he does is remove a certain illusion — the illusion that our motivations are always as pure or self-contained as we’d like to believe.

This Adlerian lens becomes even sharper when I turn it toward my role as a coach.

What are my true motives?

On the surface, helping looks noble. Supportive. Generous. And often it is. But Adler asks an interesting question beneath that surface: Whose task is this, really?

What he means by this, is it really my task to improve someone else? When I rush to help, to advise, to guide, I have to ask myself what I’m actually attached to. Am I supporting someone else’s growth, or am I trying to feel effective, competent, needed, or validated? How do I feel when someone ignores my advice or doesn’t get the result I hoped they would?

Sometimes helping isn’t really about the other person at all. It’s about reducing my own discomfort — discomfort with uncertainty, with not knowing, with sitting alongside someone else’s struggle without trying to fix it.

From an Adlerian perspective, this is a subtle form of control. Not malicious. Not intentional. But still a crossing of boundaries. When I take responsibility for outcomes that aren’t mine, I may feel important, but at what cost?

This connects to something I’ve been reflecting on a lot lately…

The weight of being “the one who should know.”

As a coach, there’s an unspoken expectation, often internal, that I should be regulated, grounded and have things figured out. But Adler dismantles the idea that psychological health comes from superiority or having all the answers.

For him, mental health is rooted in equality — standing alongside others, not above them.

The more tightly I cling to the identity of “the one who knows,” the more I feel that quiet pressure to maintain an image. And the more that happens, the less honest my relationships become, even when everything looks fine on the surface.

So where does this leave me?

Not with answers, but with awareness.

I’m starting to notice how often my striving, my helping, and my self-improvement efforts are shaped by a desire for approval or significance. Rather than trying to eliminate that, which feels unrealistic, I’m experimenting with something simpler and more difficult.

Pausing before offering help. Letting others misunderstand me. Letting achievement be less about status and more about participation.

Adler talks about the courage to be disliked. I’m beginning to see that this courage isn’t dramatic or rebellious. It’s quiet. It’s the courage to stop managing impressions, to stop proving my worth, and to stop confusing importance with meaning.

I don’t know where this inquiry ultimately leads. But for the first time in a while, I feel like I’m relating to myself — and hopefully to others — a little more honestly.

And that feels like a good place to begin.

To be continued…

Adam